- 74 Mount Street, Heidelberg, VIC, 3084

- Monday to Friday: 9am to 5pm

Acoustic Shock and Tensor Tympani Syndrome (TTS)

-

DWM Audiology > Acoustic Shock and Tensor Tympani Syndrome (TTS)

Acoustic Shock

Acoustic shock is an involuntary fright/psychological trauma reaction to a sudden, loud, unexpected/unavoidable sound near the ears leading to a characteristic cluster of involuntary, highly specific neurophysiological symptoms1-12, as well as symptoms consistent with trauma and fright.

If these symptoms persist beyond two months, an acoustic shock becomes an acoustic shock disorder or acoustic shock injury, generally due to the development of hyperacusis (abnormal sound intolerance). Acoustic shock disorder has been recognised legally in Australia and the UK as a legitimate condition.

Background

Call centre staff using a telephone headset or handset are vulnerable to acoustic shock because of the increased likelihood of exposure, close to their ear(s), of a sudden unexpected loud sound (acoustic incident) randomly transmitted via the telephone line. In the early 1990s, co-inciding with the rapid growth of call centres in Australia, increasing numbers of employees were reporting this highly specific cluster of symptoms. A similar pattern was being noticed overseas, and the term acoustic shock was coined to identify this symptom cluster.

With the large numbers of call centres, health practitioners are increasingly likely to encounter acoustic shock symptoms in their patients. This has significant medical, clinical and medico-legal implications.

The limited research on acoustic shock has mainly focused on call centre employees.10-12 However, acoustic incidents can occur anywhere, nor is this exclusively a workplace condition.4 Many musicians have been seen at our clinic with acoustic shock disorder. A viola player in an opera orchestra in the UK developed acoustic shock disorder from the (unavoidable) sound of multiple brass instruments in close proximity during a rehearsal in the confined space of an orchestral pit. He won his court case.

Any patient who has developed tinnitus and hyperacusis, particularly following exposure to a sudden unexpected loud sound or associated with a highly traumatic experience, may report at least some of these symptoms.

Acoustic shock disorder symptoms

Typically, people experiencing an acoustic shock describe it as like being stabbed or electrocuted in the ear.

The neurophysiological symptoms of acoustic shock can include some or all of the following:

- aural pain: a stabbing pain and/or a dull earache

- a severe startle reaction, often with a head and neck jerk

- aural sensations of blockage/pressure/tympanic fluttering

- a subjective sensation of muffled/distorted hearing

- other sensations including pain/burning/numbness around the ear/cheek/jaw/side of the neck

- tinnitus, hyperacusis

- mild vertigo and nausea

- headache

The symptoms are involuntary, unpleasant, frightening and can be deeply traumatic; they can range from mild to severe; and be of short, temporary duration or persistent. If symptoms persist, a range of emotional reactions including PTSD, anxiety and depression can develop.

What causes acoustic shock disorder symptoms?

The immediate symptoms of acoustic shock are considered to be a direct consequence of excessive reflex contractions of both the middle ear muscles caused by a strong startle response to a loud acoustic incident.

For some people, there are no immediate symptoms, but a delayed threat response to the acoustic incident triggers hyperacusis. This is more likely to occur when the acoustic incident is unavoidable rather than unexpected. In some call centre cases, acoustic shock symptoms can develop as a result of cumulative exposure to sustained headset use, without a specific acoustic incident being identified.

Tensor tympani syndrome (TTS)

Tensor tympani syndrome (TTS) has been proposed as the neurophysiological mechanism causing most of the persistent acoustic shock disorder symptoms. These symptoms can become sound-induced or sound-aggravated. TTS in acoustic shock and hyperacusis patients is not widely recognised or understood in the medical profession and has only recently been objectively verified.1,2

Once TTS has become established, the range of sounds that could elicit this involuntary response can increase to include many everyday sounds, as a result of the development and escalation of hyperacusis.

Hearing assessments

Acoustic shock disorder generally does not result in a hearing loss, although if present it tends not to follow the typical high frequency pattern of a noise induced hearing injury but affects low and mid frequency sensorineural and/or conductive hearing.

Audiological testing needs to be carried out with understanding and care. For patients with severe acoustic shock symptoms, listening to sounds via headphones can be highly threatening, potentially leading to symptom aggravation. Patients are understandably worried they have sustained damage to their ear/hearing and normal Tympanometry results can provide significant reassurance.

Suprathreshold audiological testing is ideally kept to a minimum. Loudness discomfort testing, and in particular acoustic reflex testing due to the volume levels required, is contraindicated. Some acoustic shock disorder patients have unfortunately had their symptoms permanently exacerbated as a result of a traumatic response to acoustic reflex testing.

Differential diagnosis of acoustic shock

On examination of the affected ear, the ear canal and tympanic membrane generally appear healthy and normal.

TTS symptoms can be readily confused with Eustachian tube dysfunction, middle/inner ear pathology or TMJ dysfunction. TTS has been implicated as a major cause of referred ear pain and other symptoms in and around the ear in patients with TMJ dysfunction. In those patients, their TTS symptoms will not be sound-induced or sound-aggravated. An ENT Specialist investigation or referral to a TMJ Specialist is recommended to exclude these possibilities. If severe vertigo is reported a perilymph fistula needs to be excluded.

Acoustic shock needs to be distinguished from and is different to cochlear damage from noise (acoustic trauma), potentially causing a noise induced hearing loss. It is possible for the acoustic incident to be loud enough to cause both an acoustic shock + noise damage.

Persistent TTS will not harm the ear or the hearing, although in severe cases may cause inflammation of the trigeminal nerve innervating the tensor tympani muscle, causing sound-induced or sound-aggravated sharp stabbing neuropathic aural pain, and symptoms of burning and numbness in and around the ear.

Acoustic shock disorder symptoms are not readily objectively measurable, so an experienced clinician makes a considered diagnosis on the basis of a thorough case history noting symptom onset, persistence and escalation over time; and their link with exposure to intolerable (or difficult to tolerate) sounds. If they have developed in association with acoustic incident exposure and/or hyperacusis is present, it is likely that they are a result of TTS. The symptoms are remarkably consistent.

Significant malingering is rare in acoustic shock disorder patients. Most patients are bewildered and frightened by their symptoms and desperate to recover.

Acoustic shock treatment

An acoustic shock disorder patient is vulnerable to a significant exacerbation of their symptoms should they be exposed to any unexpected, sudden onset, loud sound via a headset worn on either the affected ear or their other ear. After seeing this occur in a number of our acoustic shock disorder patients with persistent symptoms, the advice from our clinic is that these patients should not return to headset or telephone duties until their symptoms have resolved. A gently graded return to work can then be carried out with handset use initially on the opposite ear.

Myriam Westcott developed this information on acoustic shock disorder and TTS after evaluating and providing therapy for over 250 acoustic shock disorder patients.

References (1-12):

- Fournier P, Paleressompoulle D, Esteve Fraysse M-J, Paolino F, Devèze A, Venail F, Noreña A. Exploring the middle ear function in patients with a cluster of symptoms including tinnitus, hyperacusis, ear fullness and/or pain. Hearing Research 422 (2022) 108519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2022.108519

- Fournier P, Paquette S, Paleressompoulle D , Paolino F, Devèze A, Noreña A. Contraction of the stapedius and tensor tympani muscles explored by tympanometry and pressure measurement in the external auditory canal. Hearing Research 420 (2022) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2022.108519

- Noreña AJ, Fournier P, Londero A, Ponsot D, Charpentier N. An Integrative Model Accounting for the Symptom Cluster Triggered After an Acoustic Shock. Trends Hearing 2018 Jan-Dec; 22: 2331216518801725

- Londero A, Charpentier N, Ponsot D, Fournier P, Pezard L and Noreña AJ. A Case of Acoustic Shock with Post-trauma Trigeminal- Autonomic Activation. 2017. Front Neurol. 8:420

- Westcott M: “Middle Ear Myoclonus and Tonic Tensor Tympani Syndrome”. Chapter in “Tinnitus: Clinical and Research Perspectives” edited by D M Baguley, M Fagelson, Plural Publishing Inc, 2015.

- Westcott M. Acoustic Shock Disorder. Tinnitus Discovery – Asia and Pacific Tinnitus Symposium, Auckland, September 2009, NZMJ 19 March 2010, Vol 123 No 1311

- M Westcott et al. Tonic Tensor Tympani Syndrome (TTTS) in Tinnitus and Hyperacusis Patients: A Multi-Clinic Prevalence Study. Noise and Health Journal, Mar-Apr 2013, Volume 15, Issue 63 pp117-128.

- McFerran DJ, Baguley DM. Acoustic shock. J Laryngol Otol. 2007 Apr;121(4):301-5

- Westcott, M. Acoustic Shock Injury. Acta Otol Supplement, 556, 2006: 54-58.

- Patuzzi R. Acute aural trauma in users of telephone headsets and handsets. In: Ching T, ed. Abstracts of XXVI International Congress of Audiology, Melbourne, 17_21 March 2002. Aust N Z J Audiol (spec ed) 2002;23:132.

- Milhinch J. One hundred cases in Australian Call centres. Risking Acoustic Shock. A seminar on acoustic trauma from headsets in call centres. Fremantle, Australia, 18-19 September 2001. Morwell: Ear Associates Pty Ltd, 2001.

- Patuzzi R, Milhinch J, Doyle J. Acute aural trauma in users of telephone headsets and handsets. Neuro-Otological Society of Australia Annual Conference, Melbourne, 2000 (personal communication).

Our Services

Hearing Services

Hearing loss is common, particularly as you become older. In Australia, research shows 1 in 5 people over 60 years old will have a hearing loss

Read More

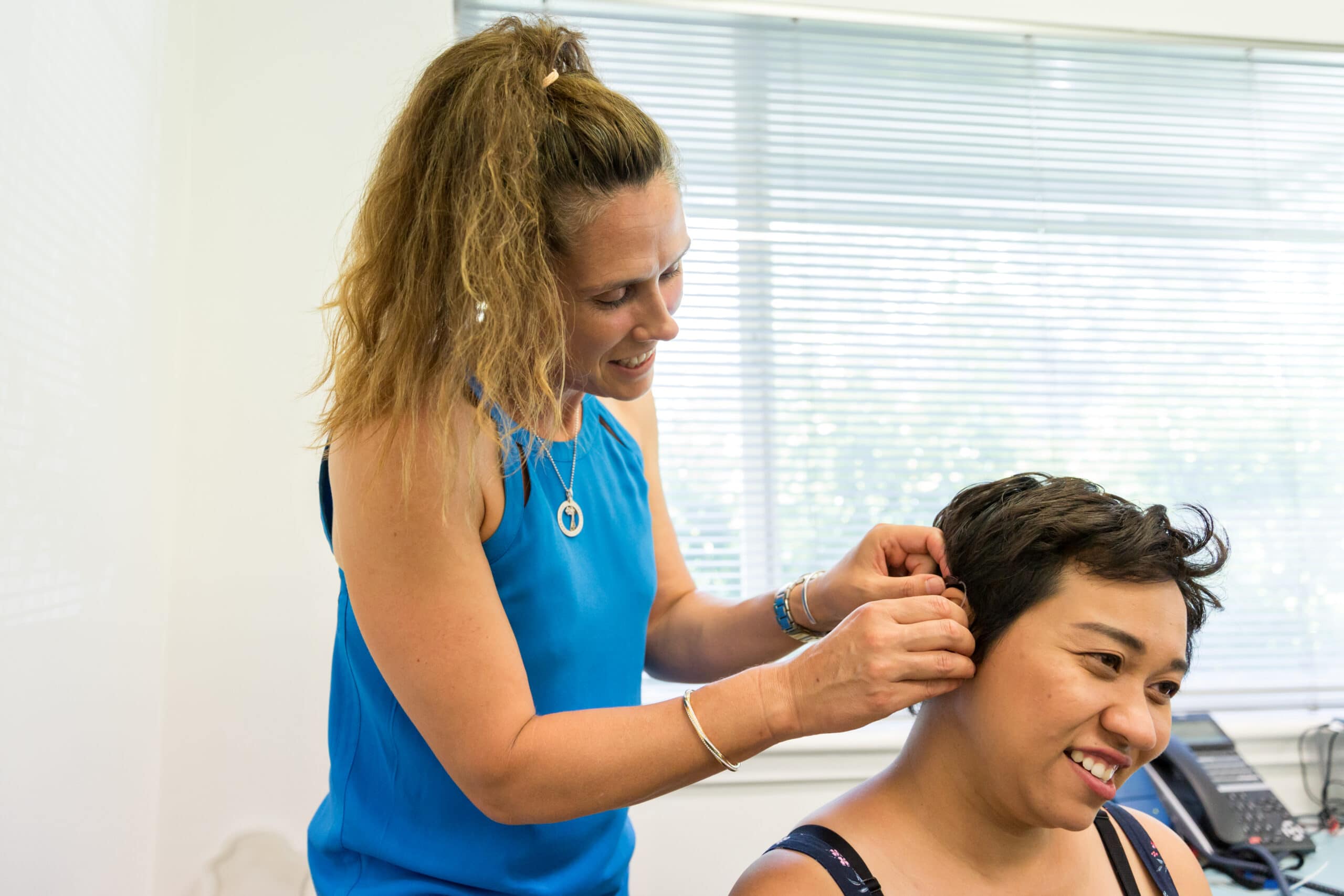

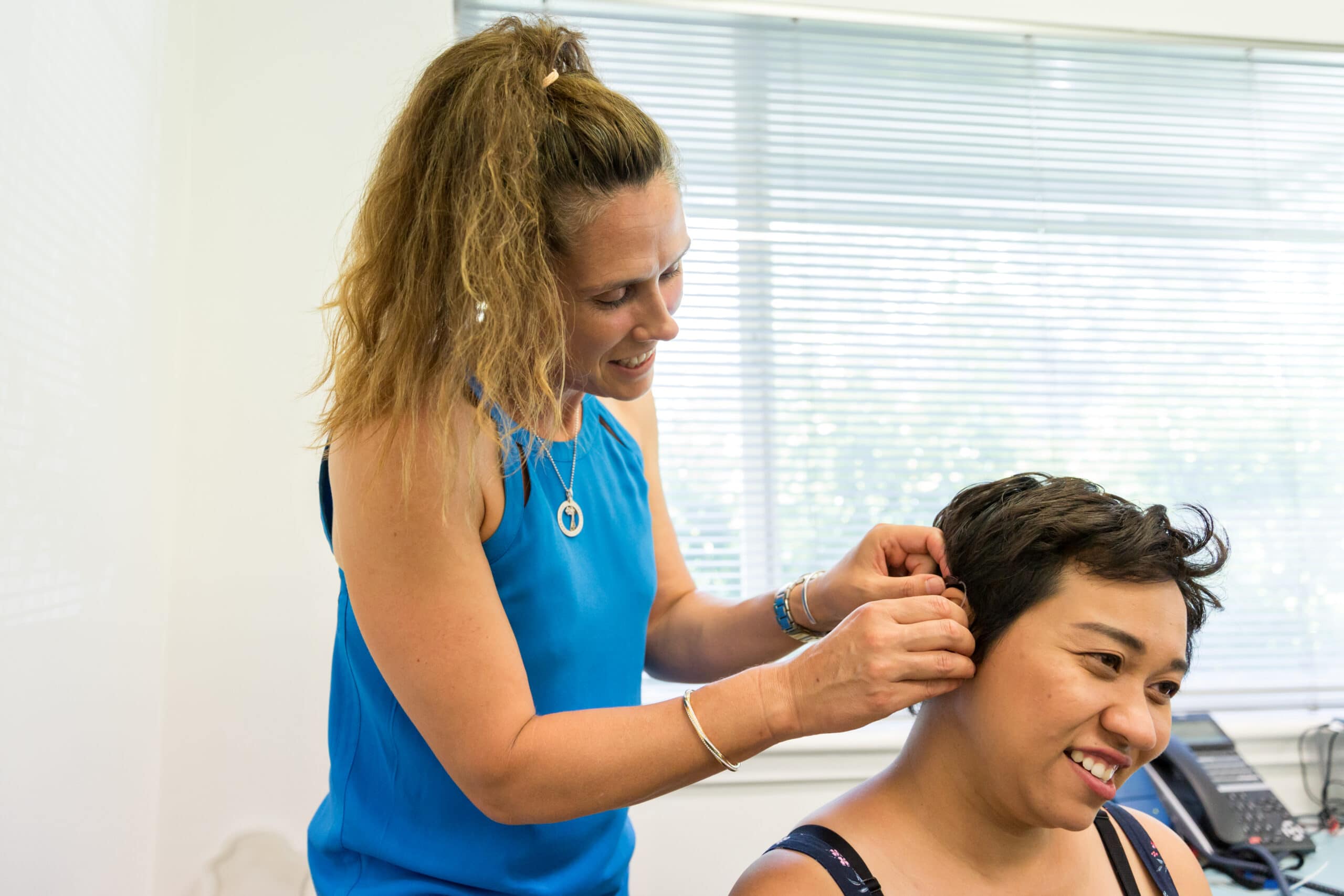

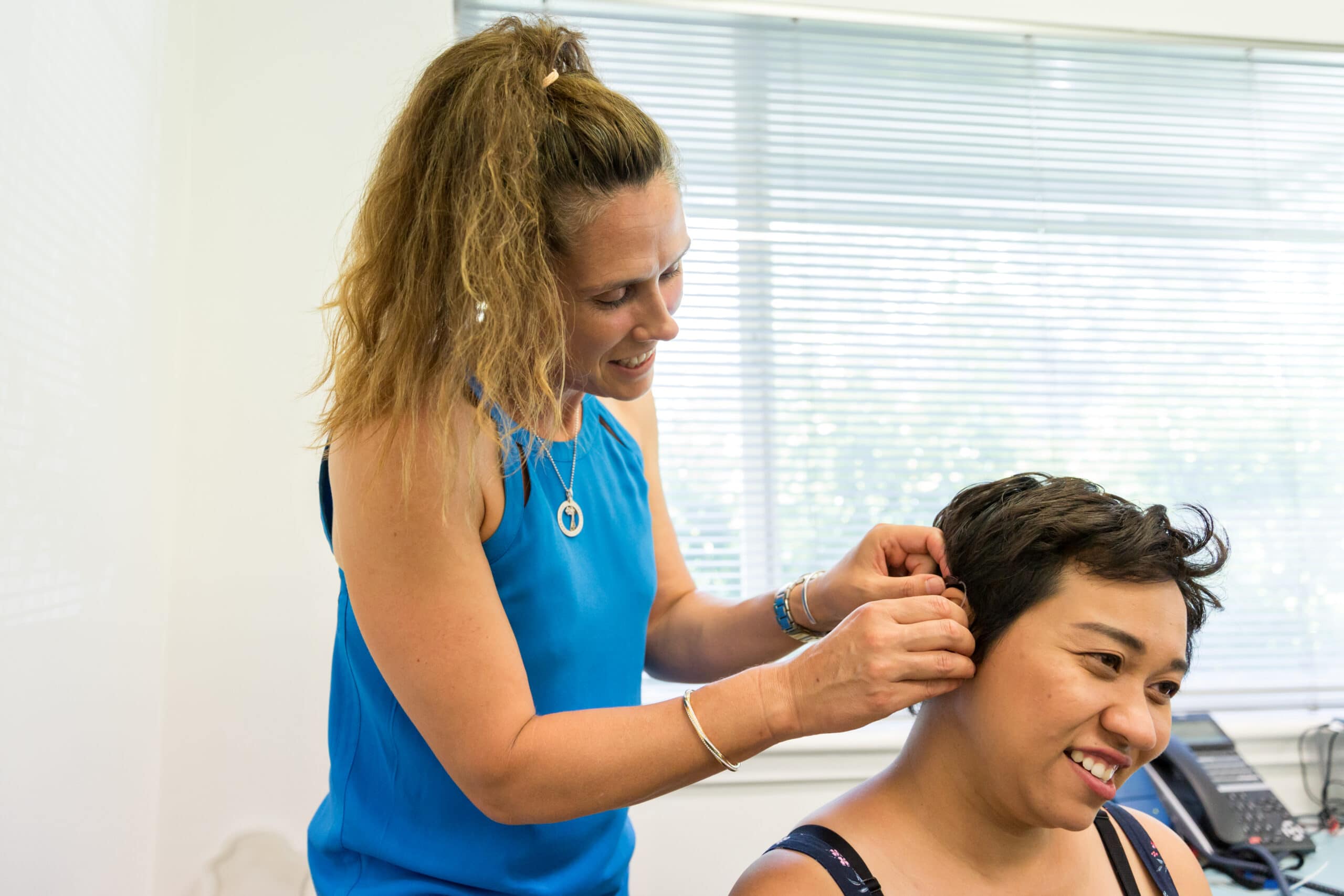

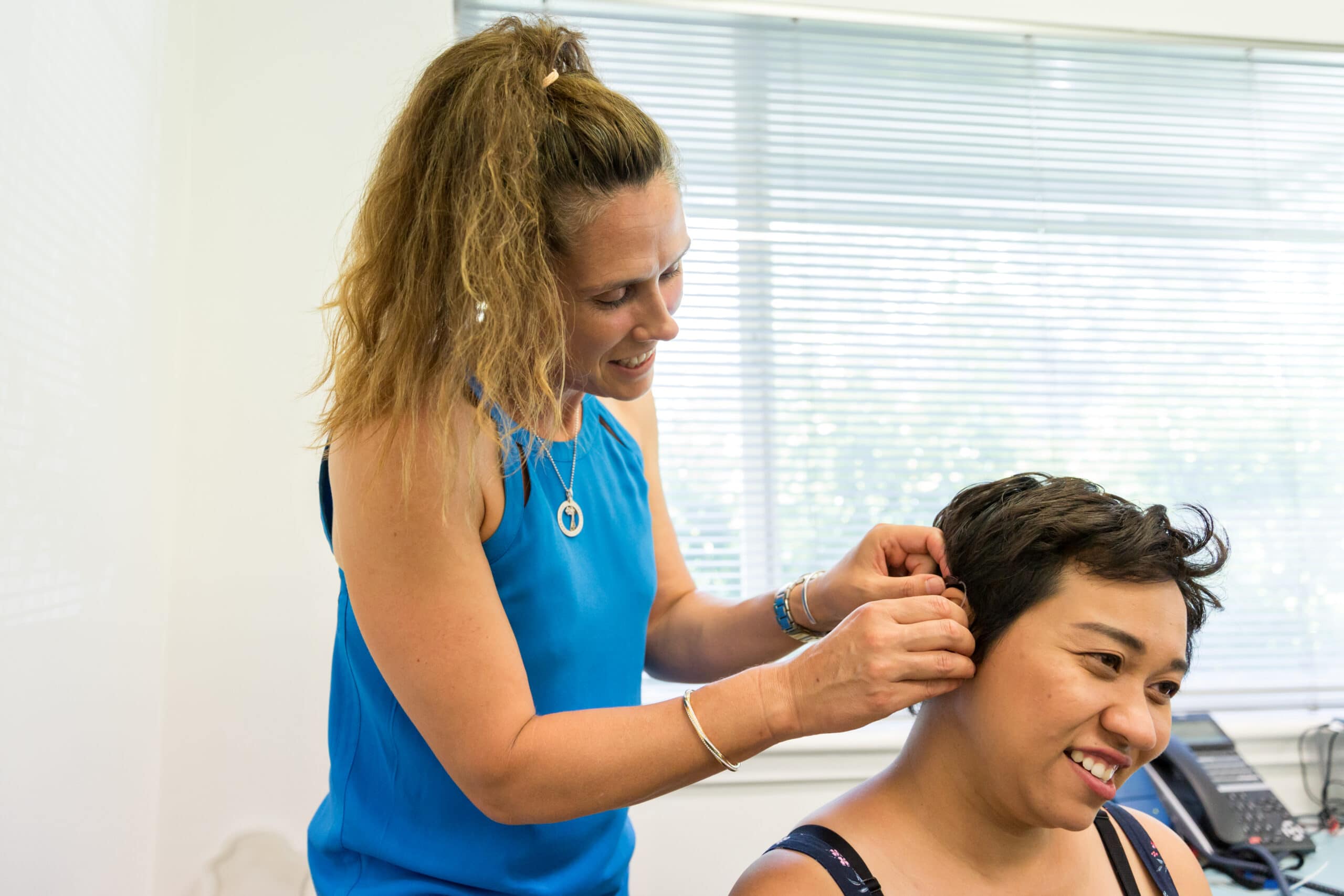

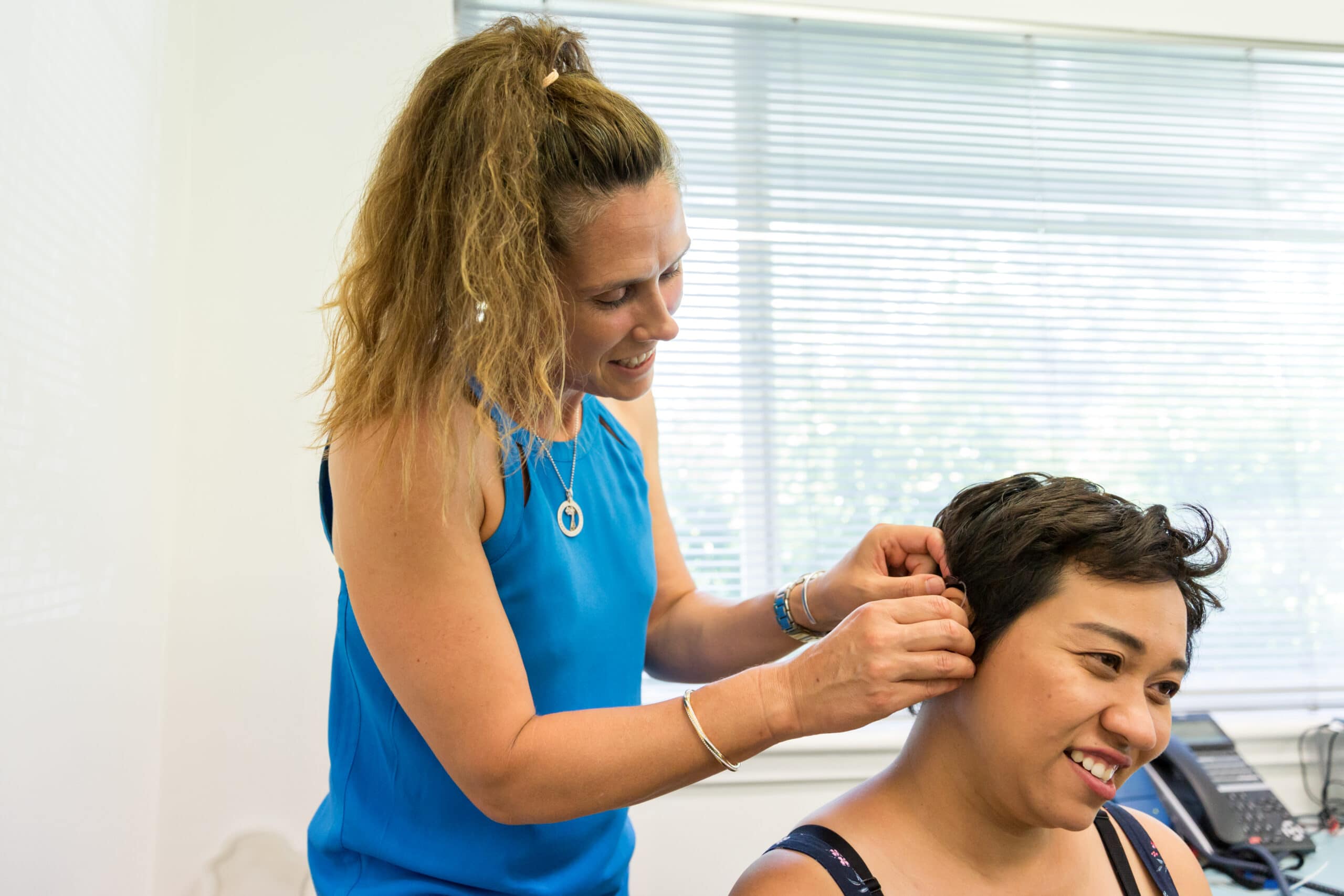

Hearing Aids

We believe that our patients should be given the necessary information and guidance to make their own hearing aid decisions.

Read More

Tinnitus

DWM Audiology provides an individualised program to assist you in achieving tinnitus habituation and management.

Read More

Hyperacusis & Misophonia

We provide a unique, individualised program to assist you in achieving increased tolerance to everyday sound,

Read More

Acoustic Shock

Our Audiology practice provides unique expertise in the evaluation and management of acoustic shock patients and in acoustic shock workplace consultancy

Read More

Auditory Processing

A comprehensive management program can be put together, once a person's specific auditory processing weaknesses have been identified.

Read More

Hearing Tests for Kids

Hearing difficulties in school age children are known to have a significant impact on their social, behavioural and academic growth.

Read More

Support for Musicians

We are preferred audiologists for the specialised impression taking for in-ear monitors fitted by Ultimate Ears.

Read More